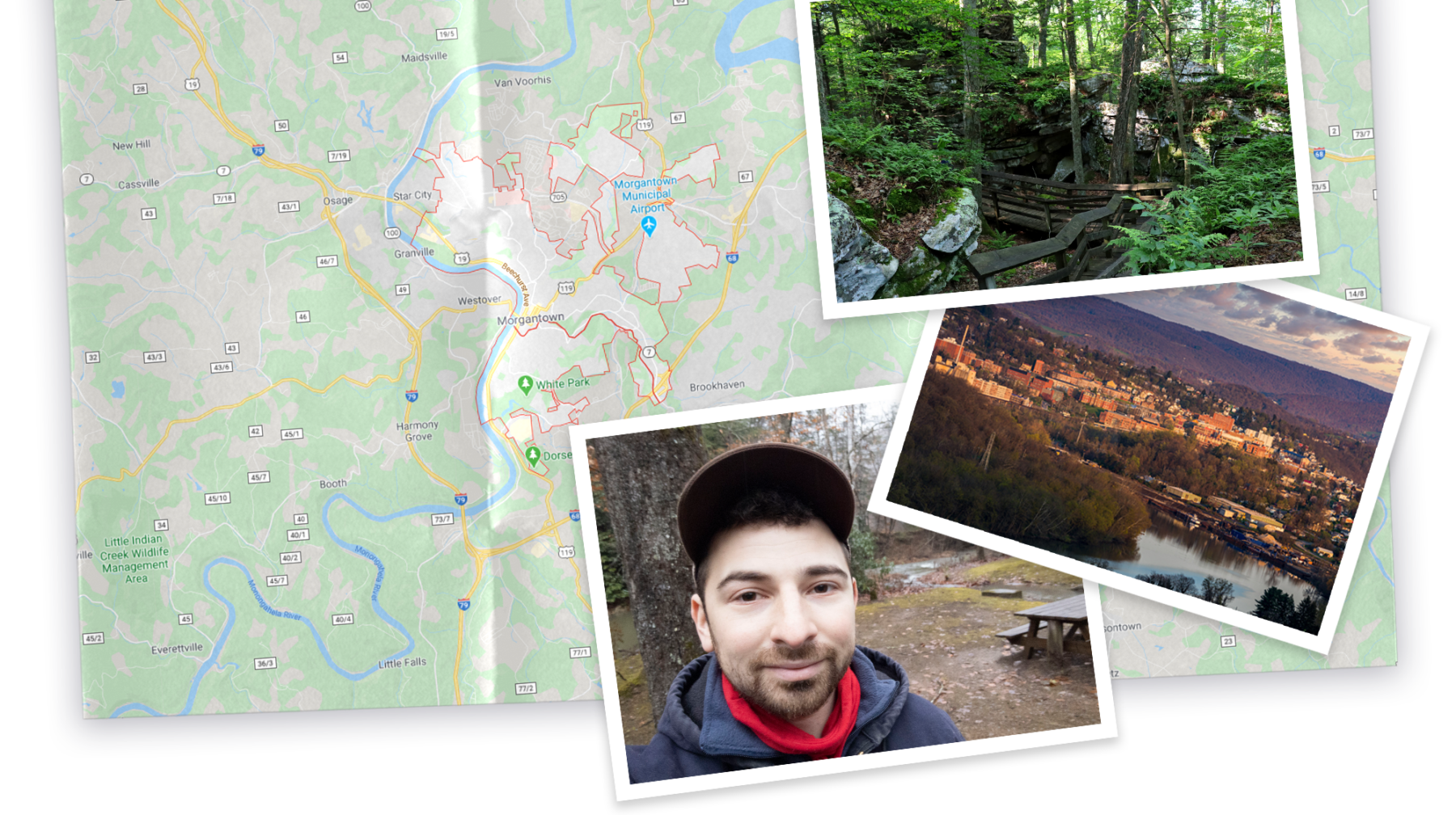

“I’m used to there always being a creek running by the road…I think I’ve always found peace in the woods and the water,” says Becker of his decision to return home to Appalachia.

Photos courtesy of Benny Becker and from iStock

Raising Voices

“If I’m not surprised while I’m making the story, then I didn’t learn anything and probably neither will the people who I’m telling it to.”

The most famous songs about West Virginia are from the perspective of someone who’s left, says Benny Becker.

“It’s just like a normal part [of] the experience to expect to leave,” explains Becker, who grew up in Morgantown, West Virginia. “If you want to get to good things, and you’re from West Virginia … there’s kind of an expectation that you will follow where jobs are.”

That’s what Becker did, initially. After high school he left Appalachia for the Northeast to study linguistics at Brown. During a summer break Becker spent teaching English in Panama, he fell in love with WNYC’s science podcast “Radiolab,” and in turn with audio as a medium for telling stories. Since then, Becker has followed various media opportunities, eventually bringing him to Cambridge, Massachusetts, as an Abrams Nieman Fellow for Local Investigative Journalism at Harvard in 2019.

“Audio lends itself to being able to dive deeply into things, slow down a little bit, and broaden it … it’s meant for people whose hands are distracted, whose eyes are distracted, but their minds are not. That’s a good way to get people to engage with big ideas.”

“Clean Water Wanted: Contaminated Wells And The Legacy Of Fossil Fuel Extraction”

transcript

Transcript:

[The sound of water splashing]

Chauncy Easterling:

Here’s the water. That’s all coming straight out of that mine’s right there. It’s got a dingy, oily filmy look. This is what always happens around here. When it don’t produce money for them no more, they walk off and leave it. And who’s stuck with it? We are.

Melissa Easterling:

Hello. I’m Melissa

Chauncy Easterling:

I’m Chauncy Easterling.

Melissa Easterling:

We’re from McDowell County, West Virginia. We’re having a lot of problems with our water.

Chauncy Easterling:

And they think that’s what killed her dad.

Timothy:

You see that one with the tombstone up there, that’s my papa. Used to be my papa.

Chauncy Easterling:

One of the things on his death certificate was kidney failure, and that was arsenic that was in the water.

Melissa Easterling:

Our water first had a funny smell to it. And then it got real dingy.

Chauncy Easterling:

You couldn’t get it on you. It’d eat your skin.

Melissa Easterling:

We contacted the health department and he gave us a list of what was in it. And then we went on out to ridge testing.

Chauncy Easterling:

Every bit of what we’ve had tested in a good two mile radius around us, we’ve been told not to drink the water, not to bathe in the water, not to touch the water.

Melissa Easterling:

Our neighbor out there that’s got a lot of lead in it. She still drinks it even though she knows that it’s bad.

Chauncy Easterling:

We got to have some help and they need to clean this mess up before a lot more people get killed, die from it. I mean, you don’t really know the extent of this. But til they do something like that, we need help with city water right down in here.

Mavis Brewster:

I’m Mavis Brewster, general manager for McDowell County Public Service District. Those residents are desperate for water service. We’ve been trying for several years and have not gotten funding for that one. Federal funds and state funds have not been as plentiful as they used to be and every year we’re competing against ourselves and against everyone else that needs money.

Chauncy Easterling:

You see, it’s going to happen everywhere because these are some of the wells, when they first started finding gas around here… Kentucky, Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, you can go anywhere and find situations like this right here.

Nina McCoy:

I’m Nina McCoy. I’m from Inez, Kentucky in Martin County. After what happened in Flint, it was like, “Oh my gosh, there’s other people who have water problems.” We all need to get together on this because this is a problem nationwide.

Nicole Horseherder:

My name is Nicole Horseherder, the English equivalent of Diné is Navajo. My family for generations have lived on Black Mesa. On the northern end of the plateau at Peabody, they used to operate two mines. Our springs and seeps don’t produce and the water’s contaminated. What’s going to be here in 20 years. If it’s not going to be here and it’s a life giving element, there’s going to be no life here.

Chauncy Easterling:

We use to drink the water out of that creek. Now you can’t do it. It’s contaminated. And God knows our children’s children won’t be able to go down there and swim in that creek or fish in that creek. The money don’t last but money will fix the problems here and fix it to where the land will last. But if we don’t get no help, none of it’s going to get fixed. That’s the big situation.

Much of Becker’s storytelling work has been focused on creating a platform for audiences to hear — literally — voices that they otherwise wouldn’t, mostly Appalachian. “There’s a long history of disrespect towards people who carry signifiers of being from the mountains,” Becker says, which includes accents and diction that are rarely heard on national media. By providing minimal narration, Becker’s audio storytelling approach lets Appalachians shape their own narratives and introduces national audiences to often-marginalized voices.

Since May 2020, Becker has been working as a media educator at Appalshop, an Eastern-Kentucky-based nonprofit started as a community film workshop to boost local economies by teaching filmmaking to young Appalachians. The organization’s vast archive includes films about Appalachian music legends, the coal miners’ strike in 1984 against coal company A.T. Massey, and the underpaid, overworked women employed in the fast food industry in Kentucky.

“People [at Appalshop], once they were trained, were like … ‘I want to stay here. No one’s telling our stories from here.’ And that’s kind of how this locally rooted media making tradition got started, but then they grew.”

Throughout the summer of 2020, Becker’s 19-to-22-year-old students worked on a series of audio pieces, which together were titled “A Mask on the Mountains: Dimensions of Covid in Appalachia.” Their stories range from a look at the pandemic’s impact on rural foster care and foster families to what the cancellation of Appalachian summer music festivals meant for local musicians in a region with such a deep tradition of local music.

At the Appalachian Media Institute, part of Appalshop in Kentucky, Becker teaches a youth media production class.

Photo courtesy of Benny Becker

Becker hopes that building up the local media ecosystem through education and training will uplift a broad range of voices in the region.

“Offering paid training to young people feels like the way to open the door to more voices,” Becker says of his transition into media education. Becker’s hope is that these trainings will not only equip young Appalachians to tell important local stories, but will also empower them to make the important decisions behind which stories get told at all. And maybe persuade some of them to stay.

One challenge that many up-and-coming freelance journalists face is lack of funding, which means they often end up self-funding their early work. “It’s so normalized that people are working for free and burning their own savings,” Becker explains. And those who can’t afford to work for free have even fewer options when it comes to getting a foot in the door. Becker sees providing paid opportunities for young media makers in the region as the key to creating a more equitable field and telling stories that may otherwise go unheard.

Ultimately, Becker says, what his students do is up to them — he just wants to provide them with choices. “I’m not as invested in what it is that they will do, as much as I feel good about giving them this set of tools and options, which I think can be adapted and useful to a lot of things.”

When it comes to his own work, Becker says, “I still like doing interviews, I like making stories, but I feel more passionate about helping to get a wider set of perspectives involved in [media], and especially a more diverse group of younger people. … It’s been exciting to see what they’re excited about making and telling and doing.”

This story is part of the To Serve Better series, exploring connections between Harvard and neighborhoods across the United States.