Eve L. Ewing with Nate Marshall at the second annual Chicago Poetry Block Party.

Photo by Sarah-Ji

Poetry in motion

“What I have found over and over is [that] if you give people an accessible entry point [to the arts], they’ll take to it with great enthusiasm and great excitement.”

From sociological research to books of poetry, from block parties to podcasts, plays, children’s books, and even Marvel comics, Eve L. Ewing’s, Ed.M. ’13, Ed.D. ’16, work is rooted in an enduring focus on community engagement.

Ewing, lifelong Chicagoan, sociologist at the University of Chicago, and graduate of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, describes her “one project with many parts” as an effort to reframe conversations to center those who are often left out — people of color, low-income communities, those who have been most impacted by years of social, political, and economic injustices yet remain excluded from the dialogue and narrative surrounding them. “Real inclusivity,” says Ewing, “means an understanding of history and an understanding of power. And a radical willingness to address those things with courage.”

Ewing’s is a commitment rooted to a place and its people. Raised in Chicago and a graduate of its public school system (which later became the subject of her scholarship), Ewing is unwavering in her dedication to her hometown. Although the themes she explores in her work, like systemic racism, are hardly unique to the city, Ewing often chooses to address them through the lens of Chicago — to tell its stories, uplift its heroes, and imagine its future.

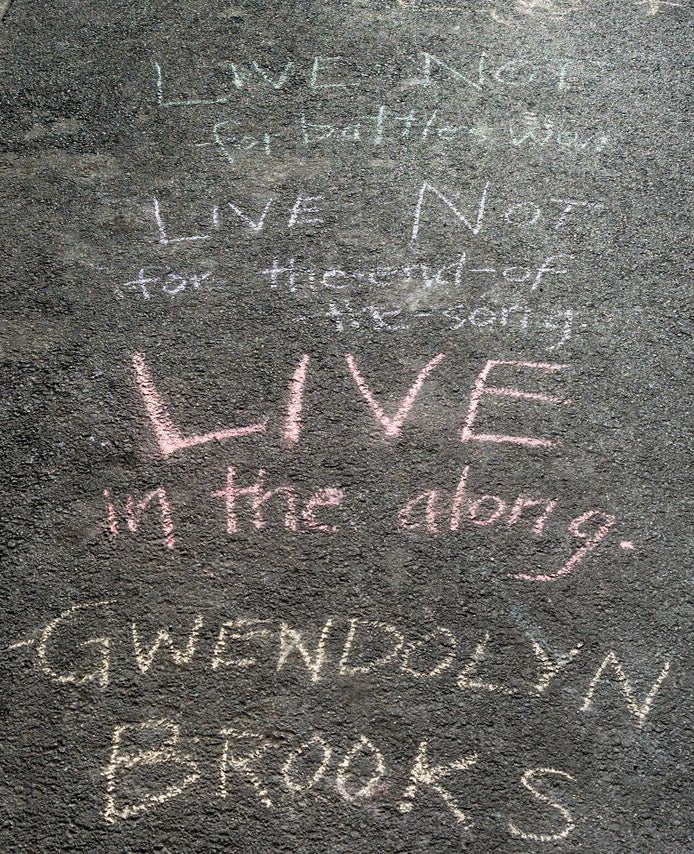

“It’s the notion of just literally writing about the street where you live and the people around you and your experiences,” Ewing explains, citing Chicago literary icon Gwendolyn Brooks as an early role model who exemplifies this ethic. “[This idea has] been really instructive in my life. … I see myself as part of a literary legacy that is really deeply rooted here, and I [try] to create work that is representative of and accountable to people in Chicago.”

Take Ewing’s recent book of poetry, “1919,” which grapples with the bloody Chicago riots triggered by the lynching of a black teen at an unofficially segregated beach, aiming to bring the history out of academic circles to a more popular audience (it also includes a teaching guide). Or consider “No Blue Memories,” a multimedia play celebrating Gwendolyn Brooks that was performed, for free, for public school students and others throughout Chicago. Perhaps the best example, though, is the annual Chicago Poetry Block Party, which Ewing co-founded with two fellow Chicagoans, poet Nate Marshall and Poetry Foundation director of community and foundation relations Ydalmi Noriega.

Images from the 2016 and 2018 Chicago Poetry Block Party.

Photos by Sarah-Ji

The free event, now in its fifth year, takes place in a different Chicago neighborhood each summer, challenging popular conceptions of a poetry festival by taking it “out of a university or a conference center and plac[ing] it squarely on a city block.” The Poetry Block Party features the many poetry readings and workshops one might expect at a literary event, but it also includes some less conventional offerings like a piñata and bouncy house — and a voting registration table. Attendees can explore form and rhythm, and they can learn where the nearest HIV testing centers are, or how to get help doing their taxes if they’re low income. When the event is over, they can take home poetry journals, books, a new library card, or free condoms.

“A lot of times we just assume that average people won’t like certain types of things or won’t understand certain types of things,” Ewing explains. “I feel that way about poetry. I feel that way about complicated academic topics.” She notes that often, artists and academics have “abdicated our responsibility as practitioners” to engage with people in good faith and bring them into the conversation.

“We write them off like, well, they won’t get it or they won’t be interested. And what I have found over and over is if you give people an accessible entry point [to the arts], they’ll take to it with great enthusiasm and great excitement. I’ve always had that theory, and it’s at the Block Party [where] it’s been reaffirmed over and over.”

This story is part of the To Serve Better series, exploring connections between Harvard and neighborhoods across the United States.